The Octopus Deploy Story: Building to $80M ARR Without VC

Paul and Sonia Stovell bootstrapped Octopus Deploy for a decade before taking investment from Insight Partners. The company now does $80M in annual revenue and is flying.

Paul Stovell and his wife Sonia co-founded and grew Octopus Deploy into one of the world’s leading continuous delivery tools, despite not raising external venture capital until almost a decade into the journey. They recently closed a A$45m round with Insight Partners, boosting their valuation to A$880m.

In this story we dive into:

Getting into the magic of computers after growing up in a steel mining town

Hacking on nights and weekends to build and grow the first version

Being scared to charge anyone in case they didn’t want to pay

How focusing on sustainable growth and profitability produced an outsized company

SH: Tell me who Paul is in 30 seconds or less.

PS: I’m a dad with three kids and a Westie pup. I like to build things, and I have a strong tendency towards self-reliance. If there’s something that needs to be done and it’s conceivable that I could do it myself, I would always lean towards doing it myself rather than hiring somebody or outsourcing the problem. I’ve spent 13 years building Octopus and was a self-taught software engineer before that.

SH: You bootstrapped Octopus Deploy for most of its existence. Did you have any history of entrepreneurship before that?

PS: Not really. I grew up in Whyalla, a steel mining town. The whole economy was dependent on the steel mill. Growing up, every adult either worked there or was involved in a business related to it.

But by the mid-90s, the internet had come along and computers were in every house. Like all 15-year-olds, you start playing video games and then you feel like this thing is really magical.

Around 16 I got interested in how computers and software worked. It was like discovering the unlimited Lego set. With most hobbies there’s some cost involved, but with software, once you have a computer, everything is free. It’s like having a billion Lego bricks at your disposal. The only limiting factor is your time and creativity. For a teenager with not much else to be interested in, that was an amazing discovery.

SH: This was during the dot-com boom and bust?

PS: Yeah, this was the dot-com boom. I was still a teenager so I might be wrong with some facts, but all this money had flown into software in the early 2000s, and then that money suddenly came out again as we realised people weren’t going to buy pets on the internet.

What was left around 2003 were a handful of independent people who loved software and were writing it because it was fun to write. Those companies who hired their nephew as head of IT because he had a computer? All of that collapsed. The people who weren’t there for the love of the craft left.

The only entrepreneurial activity left were people like Joel Spolsky and Eric Sink running small boutique software businesses. I fell in love with that because you realise software is unlimited. It’s only limited by your creativity, and you can make an income out of it. I started developing websites for people around 17, then moved into developing apps and open source things.

SH: How did you get to the idea for Octopus Deploy?

PS: I was 25 when Octopus started. I’d moved to Sydney at 18 and got my first job as a software developer. I did get into university but I never enjoyed school much, so I wasn’t excited about three or four more years of it! But through the open source work I’d been doing, I found a job at a small software company in Sydney.

I learned very early that the only way to build client trust was to deliver something and get it into production quickly. Every new customer, you’d spend time setting up source control and build automation. Then you’d spend weeks trying to get something deployed to production.

Once you got something into production, the relationship with the client would really change. For the first four or five weeks, they’re giving you trust and have hopes you’ll meet their needs. But it’s not until they start seeing something in production that their hope starts to reconcile with your actual ability.

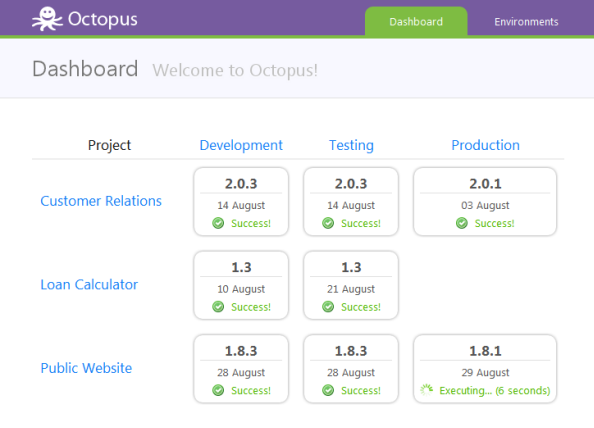

At the time, the continuous delivery book had been published and agile was a big thing. As an industry we knew that continuous delivery pipelines and getting changes into production quickly would create faster feedback loops and more successful software teams. But the reality was this was really hard to do. Getting something to production became this nightmarish process you’d do on a weekend that wasn’t documented, and that had all kinds of production access issues.

SH: So Octopus was born out of that frustration?

PS: Yeah, it was my desire to solve that through a bag of tools I’d carry around from job to job. Originally it was going to be an open source project, but I’d done open source things before and realised for this to really work, it needed good documentation because it’s running in people’s production environments. It needed a good user interface so people could use it. Those things don’t tend to work well in small-scale open source projects.

So I thought I’ll just make a little business out of it and start selling licenses.

SH: When did you start building it?

PS: By this point I’d moved to London and was contracting at Credit Suisse. I’d spend every day at the bank dealing with bad deployments, queuing up behind the ops guy to get access to production. Then at night I’d think, “I’m fed up with these issues, I’m going to solve them in this product that was becoming Octopus.”

From 2010, I started writing code for it. Through to 2012 when people started buying licenses, it was a nights and weekends hobby project.

I’d work on it on weekends, I’d blog about it. I’d been blogging for a while so I had a few people reading my blog anyway. This was at the height of blogging, and people were paying attention to what I was doing. They started using the product for free, because I was reluctant to charge for it at first. I just wanted people to use it and give me feedback.

Honestly, I was worried that if I charged for it, people wouldn’t find it valuable and wouldn’t buy it. That would be really sad. So I thought it’s better to be ignorant and not charge for it at all!

SH: How did the transition to a business happen?

PS: Through that period of the hobby project, you could buy license keys but the software didn’t require you to put them in. The software never asked for a license key, but there was still a pricing page on the website. People did it almost like a donation. The software wasn’t asking for it but they liked it so much they felt it was valuable and bought it anyway. You had this trickle of a handful of license sales every month, which was really nice positive reinforcement.

I moved back from London to Brisbane in October 2012, and that was when we thought I could either get another contracting job or turn this into a business. So we made the software start to ask for a license key. That’s when it shot up in terms of sales.

SH: Who’s “we”?

PS: My girlfriend at the time but now my wife of 14 years. As we turned it into a business, she started doing all the books. She had a finance background, so she started doing all the financial work. The moment we turned it into a business, that was the two of us working together. It was a family business for the next 10 years.

SH: I read your wife describes herself as a self-taught CFO?

PS: Yeah, much like me. She had a background in financial advice, power planning, that sort of thing. A natural talent for it, but hadn’t formally trained as an accountant or CFO. There’s something about when you’ve had a tradesperson come to your house and you watch them work. You’ll learn a lot, but you’ll also watch them do things and think, “I could do that better.” Mostly you’ll do it better because you care about it because it’s your house.

For us in starting the business, we did every little detail ourselves. We backed ourselves to figure things out and give it a go. We knew that because we cared about the result, that would make up for any lack of skill we might initially have in the task.

Brought to you by Murmar

SH: Do you remember your first paying customer?

PS: I know it had a number in the front of it, like a company name that started with a number. It was a UK travel-related company. We used to charge £500 for a license key because that was my day rate contracting at Credit Suisse. So what would happen is I’d sell that license and that would cover my day rate. Then I’d call in sick or take the day off.

That went from being one day a month to a few days and grew from there.

SH: What was it like in that first year or two?

PS: Every month we would sell a bunch of licenses. I think in the first month where we started charging, we made $8,000 or $10,000. Then it dropped to $5,000 and started to build up again. For the next two years, it got up to about $30,000 to $40,000 a month. That was the point where we thought, okay, maybe it’s time to start hiring some people.

Getting the first full-time employee was really scary because when you hire contractors, there’s an expectation the work might dry up in six months and that’s okay. When you hire someone full-time, it’s a big responsibility. We put off doing that for as long as we could. By 2014, we hired our first employee, Henrik, who’s still with us today. We grew from there.

Honestly, it wasn’t a grind. We were living together, working on Octopus together, raising kids. It was fun actually. We didn’t have high expectations or hopes. It was really a hobby business that turned into a full-time thing. If it has some customers and people find it valuable and it makes some money for a while, that’s great. That’s all it needs to be. We hadn’t raised funding. We weren’t trying to change the universe. It was just software that hopefully if people find it interesting enough, they’ll pay for it and that will sustain its development.

SH: Why didn’t you get overtaken by well-funded competitors?

PS: Through my consulting time, I knew there were a handful of products in this space. They were mostly sold by IBM and CA, so they were very expensive, and they tended to be shelfware. People would buy them because they have a contract with IBM for everything, but the software would sit on the shelf because it wasn’t all that usable or good. That was the first generation of deployment automation. Really designed to be sold to CTOs, never adopted bottom-up by practitioners.

Then you had a second generation of tools coming along that were a bit more bottom-up oriented, a bit more usable, but still expensive. But by and large, everybody in this market was building their own deployment tooling much more than they were buying anything else.

Funded startups in most IT-oriented software tend to focus a lot on the enterprise market. You often see this thing where it’s open source and then they sell the enterprise version. When you look at them, they only have 600 customers, but they all pay a million dollars each. A lot of the software market works that way. It’s free and open source or it’s a million dollars, and there’s not much in between.

So I think that’s why we worked. We went bottoms up with a reasonable price.

SH: You mentioned you grew 30-50% every year for 10 years. Was there ever tension about raising money?

PS: No, we never paid attention to it honestly. The conception of the business was that this is a family business. We’re going to build this thing, and if people find it useful, they’ll buy it.

Employees would notice and ask questions about why don’t we consider fundraising. But at the time, Octopus had been growing around 30-50% every year for 10 years. We’d been profitable for almost every one of those years. Not just a bit profitable either, but really profitable, like 30-40% profit at the end of the year. We got to $20M ARR in US dollars and never felt like more capital would have helped.

SH: In classic startup parlance, VCs might look at 30-50% growth and call it a lifestyle business?

PS: Yeah, but once you get to a million dollars, which we did in the first two years, if you sustain that 30-50% growth rate every year, at some point you’re doing a billion dollars in revenue and it’s only 20 years. To this day, the Octopus business plan is to just keep doing that. It’s a more organic rate you can keep up with.

When you’re trying to grow at 100 or 200% every year, you’re having to hire that many more people, change that many more processes. The wheels are just falling off. Even at our growth rate, it always felt like the wheels were falling off to some degree, but you can handle it better.

Your company culture is decided by the people working with you. When new people are being trained by new people, that’s really hard and the culture changes fast. If you’re only hiring 30% more people every year, they’re at least being trained by people who have been at the company for a couple of years. The company tends to be more sustainable.

SH: You didn’t have an ESOP until the Insight round, which means for the first 10 years there was no equity for staff. Was that a challenge?

PS: No. The business was already running, had revenue, and was profitable at the point we started hiring the first employees. It wasn’t like a startup where it’s “come and join the ride, we’re going to build a rocket ship, maybe we won’t have a job in two years.” By the time we hired our first person, we were covering our own needs with a lot left over.

We were quite slow about it. When we were hiring people, we were hiring people who we felt would be here for the long term, who cared about their craft and their job. We could provide some level of stability. Not the same kind as a large corporate, but certainly not the chaotic environment that a startup would have. We’re not planning to grow fast, we just plan to keep doing what we’re doing.

When they joined us, they were coming from government or consulting companies where there was no expectation of stock options and no risk associated with it. We paid really strong salaries. They’re effectively joining us for a better paying job with the same ownership structures but a more interesting set of problems to solve.

As Insight joined, that bargain changed. We introduced the stock option program and went back and looked at the years people had put in and made grants that reflected that.

SH: What made you finally decide to take investment?

PS: We started getting a lot of investor interest, not just Insight Partners, but a bunch of other firms. The thing on my mind was: what are they seeing that we’re not seeing?

After 10 years, every first of the month you’re still starting from zero. You’re still wondering, is this the last person that needs an Octopus-shaped product? You expect a business grows and then plateaus after a few years, but it just kept growing. So you start to wonder why it keeps growing and what investors are seeing.

We started to zoom out and look at the bigger picture. Every company at this point has teams of software engineers, some with really large teams. So software is eating the world. What do those software teams need? Software teams produce bugs, so Atlassian makes $2 billion a year selling Jira. Whatever they build, they deploy into production, so they spend $4 billion a year with DataDog and New Relic monitoring that software.

The entire software thing is moving changes into production. Jira tells you what to change. Making the change goes into GitHub. But the button isn’t blue until it’s deployed to production. Then DataDog tells you the website hasn’t crashed.

Getting into production is, in some ways, the hardest part of all of that. It’s why so many companies built their own deployment tooling. There’s no software team on the planet that isn’t using something for CI/CD or hasn’t built something for it. Of any team of substance, there is a CD pipeline whether you bought one or not.

We realised the limit to Octopus’s revenue isn’t tens or hundreds of millions of dollars. It’s probably in the billions. Someone will build that. If it’s not us, someone else is going to do it. Then you start to ask, well, why not us? This is where the Australian tall poppy thing comes in and you say,

“Well, because we’re not American.”

But you have to talk yourself into backing yourself. By the time Insight invested, we were eight years in and realised actually, we do have the makings of doing this.

The mistake so many people make is they get investors and they think there’s a really big business to be built in this space, and the investors think there’s a big business, only to find that there isn’t for some reason. Maybe the TAM just isn’t there. We were the opposite. We realised the TAM was there and we had just been oblivious to it.

SH: So why bring an investor on rather than continue bootstrapping?

PS: When you build your company, the first year or so you’re just writing code and building a great product. If you emailed support, I wouldn’t reply until Friday because I’d spend Monday to Thursday writing code. Customers didn’t care because the software was useful, the price was low, and the expectations were low.

As you grow bigger, there’s less and less room for not being good at things. We were good at software development but bad at support. By the time we got to $10M in revenue, we needed to be really good at support as well. By the time you get to $30M, you need to be good at marketing and sales. The stakes get higher.

We realised more and more of these things, such as sales, marketing, go-to-market, finance and tax burdens, were things we were going to have to become good at. If we were working with investors who had been on that journey before, maybe that is going to be easier rather than trying to bootstrap and figure it out from first principles. A lot of this stuff, when it comes to go-to-market, is transferable from company to company.

SH: Did Australian VCs like Blackbird or AirTree ever reach out?

PS: No, they didn’t. I think it’s because no one knew we existed. They probably emulated the Silicon Valley model of “there’s enough people trying to create startups here that if we wait, they’ll come and pitch to us.”

The Insight approach is they hire people out of college and put them to work. Your job is to build a database of every software company on the planet, get on the phone, reach out to them and learn everything you can. They find their opportunities rather than wait for them to come.

SH: To be fair, I consider myself reasonably well informed about the Australian ecosystem and I didn’t hear of you until the Insight announcement.

PS: No one did. There’s something funny about startup publicity. If you want to turn up in the paper as a startup, it almost doesn’t matter what you’re building or how interesting it is. You’ll only turn up if you’ve raised funding or you’ve done some ethical violation worthy of being called out. Until that point, they’re just not interested.

SH: How has your operating rhythm changed post-investment?

PS: It didn’t change at all. There was a bit more reporting, mostly tax or legal jurisdiction related. Our board meetings have stayed really informal. It’s once a quarter, mostly business focused. Not like what I imagine the board meetings of an insurance company would be.

When you bring investors on, they’re not operators. They may have seen other people dealing with your challenges, but they’ve never had that challenge themselves. Most investment firms have less employees than you do. The best way to work with them is to get introductions to people who have had those problems. They might say, “Hey, you should try this tactic,” but if you can say, “Can you introduce me to someone who’s tried that?” and you talk to that person, you’ll hear a very different story about did the tactic actually work, and what’s involved in executing on it.

Fundamentally, whether you follow their advice or not won’t matter at the next board meeting. What will matter is the results you’re bringing. That’s what should matter to you as a majority owner founder too. It’s about trying to find the truth of what is the best course of action here.

SH: Your rate of hiring must have increased post-funding?

PS: Not really. What changed was we’d been running Octopus really profitably because we were totally tied up in it. We started to realize there’s this really big opportunity we want to go after. We should not be so conservative that we miss out on experiments we can do to drive growth, particularly as the market we’re in was changing a bit. The go-to-market approaches we were trying were changing because customers were changing. There was a lot of experimentation needed. It changed from that point of view but not drastically.

Three Wrapup Questions

SH: What’s a book we should all read?

PS: High Output Management by Andy Grove. That’s a really good book, particularly for software engineers who move into people management roles. I think they start to focus on “My job as a software developer used to be to make stuff” to “Oh gosh, I’m managing these people, I’ve got to make them happy.” They forget the job is: you’re managing the people to make stuff. What is the job of a manager? That book answers it really well.

There’s another book called How Big Things Get Done. It gives a very beautiful description of what product development actually is and the way human knowledge gets embodied into products in a way that makes you really proud to be a product creator. It also looks into practical ways to predict and estimate projects and go about really big challenging projects. It juxtaposes things like the Empire State Building and how quickly that was built, compared to train networks in California that now take way longer and cost way more. It’s a really fascinating book.

SH: What’s a band or artist we should all listen to?

PS: My go-to when I’m doing stuff these days tends to be Paramore. I went to a concert with my 16-year-old daughter, a Paramore concert, and I think I just enjoyed going to the concert with her. But the music wasn’t too bad either.

SH: What’s a podcast we should all listen to?

PS: I tend to listen to podcasts that are a bit more politics oriented or about car restorations or whatever topic I happen to be interested in at the moment. John Anderson, the former Nationals deputy prime minister runs a really nice Australian politics-oriented podcast. I quite enjoy it too.

SH: Thanks for your time Paul!